Amongst the old records in the Tate Museum in the Mawson Building at the University of Adelaide there is some 1938 correspondence between Randall STAFFORD (who developed Coniston Station, northwest of Alice Springs, in 1923), Dr Cecil MADIGAN (Lecturer in Geology & Mineralogy, University of Adelaide) and Dr Richard THOMAS (CSIRO)

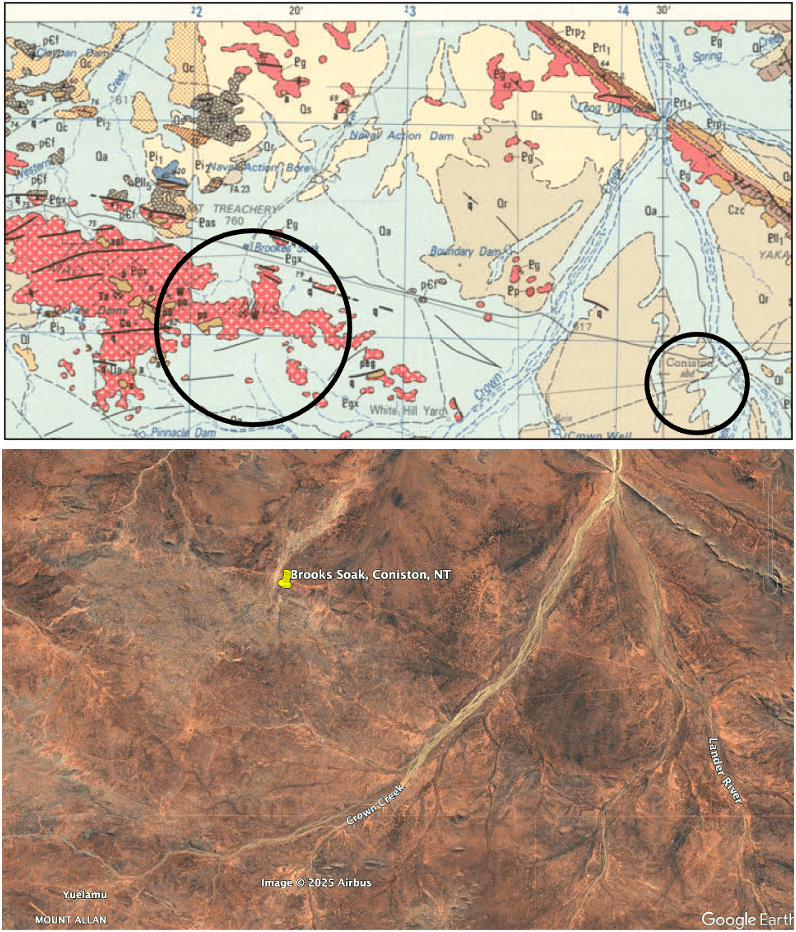

STAFFORD had written a letter to MADIGAN on 16 November 1938 accompanied by rock samples, including this pegmatite, which contains large black crystals of what Stafford thought was wolframite – (Fe,Mn)WO4, an important source of tungsten. The sample came from a hill located 4 miles south of Brooks Soak on the south side of Granite Range. Stafford asked Madigan for his opinion in advance of potentially lodging a claim over the site with the Mining Warden in Alice Springs, in partnership with Madigan. He also commented on a tin prospect in the general area, over which he proposed to peg two claims in partnership with Madigan.

It appears that Madigan sent the pegmatite sample to Richard THOMAS (CSIRO Division of Animal Nutrition; an analytical chemist and a former a student of Sir Douglas MAWSON) for detailed analysis. In a letter to Madigan dated December 3, 1938, Thomas identified the black crystals as ‘wolframite with isomorphous intergrowth of columbite’ and suggested that if there was a sufficient amount of this material identified in the field the area should be pegged. He bemoaned the fact that he and Madigan could not be in the field with Stafford to examine directly the geological relationships of the sample. He commented ‘I am more than ever convinced of the existence of many valuable and undetermined mineral associations in the granitic areas of Central Australia and this latest find confirms my faith still further.’ Finally, he asked Madigan to arrange for Stafford to send additional samples, including quartz and feldspars from the matrix of the pegmatite, for him to examine. Apart from the tungsten, iron, manganese, niobium and tantalum in the original sample, he remarked on ‘certain peculiarities’ which remained unexplained.

A telegram dated 15December 1938 from Stafford to Madigan stated: ‘APPLYING TODAY. THREE CLAIMS. TWO TWENTY ACRE ON TIN ONE. SIXTY ON LAST. SAMPLES SENT. WARDEN SAYS I MUST BE APPOINTED YOUR AGENT. REGARDS. STAFFORD.

The correspondence stops here but, lurking in the ‘background’ and 10 years earlier, Brooks Soak was the focus of a murder and a subsequent massacre, as indicated in the following extract: (https://www.commonground.org.au/article/coniston-massacre). “The Coniston Massacre occurred after a white dingo trapper, Fred Brooks, was murdered on Coniston Station in 1928. Brooks’ body was found with traditional weapons in a shallow grave. After his death, a reprisal party was formed and led on horseback by Mounted Constable George Murray. The party was made up of both civilians and police. Over a period of several months over 60 Aboriginal women, men, and children were killed at different sites. These events became known as the Coniston Massacre. Two Warlpiri men, Arkikra and Padygar, were arrested for the murder of Brooks. They were held in Darwin before being acquitted (found not guilty). There are many accounts by Aboriginal eye-witnesses that point to Kamalyarrpa Japanangka, also known as ‘Bullfrog’, as the true killer of Brooks.

In 1928, scarcity of resources like food and water had led to tensions between settlers and Aboriginal people across the Central Australian region. Accounts from 1928 highlight that Brooks was killed due to breaching Warlpiri marriage law. Brooks had been living at a waterhole called Yurrkuru, on Coniston station near a group of Warlpiri people, including Bullfrog. While Brooks did not have an Aboriginal wife, many first-person accounts highlight that he placed demands on Bullfrog’s wives, and secondary accounts suggest he may have sexually assaulted one of his wives.

Marriage law was governed by Aboriginal law during this time and breaking that law was a punishable offence. The violence that erupted at Coniston highlights the cultural misunderstandings that often created conflict throughout early colonisation. According to Warlpiri law, Bullfrog acted lawfully in exercising his traditional Aboriginal marriage law. But the consequences of the reprisal massacre were devastating for Aboriginal people across the region. Warlpiri, Anmatyerre, and Kaytetye people mourn the loss of family who were killed during the Coniston Massacre.”

Dr Tony Milnes, University of Adelaide.